For the Love of Raw Writing: Confessions of a Troglodytic Typist

I recently had the privilege of taking a fieldtrip up to Bremerton Office Machine Company, where I had the chance to meet and chat with the multitalented Paul Lundy. I dropped off my rare and valuable Olympia SM4 DeLuxe Blackjack portable typewriter for the first repair and servicing it's likely had since it was born in 1954.

Not only did Mr. Lundy find me a case that fits the beautiful machine, he explained the fascinating process of typewriter refurbishment, gave me a tour of the shop and told me the story of its venerable founder Mr. Bob Montgomery. It was like getting a behind-the-scenes look at Santa's workshop from his chief elf!

It turns out that the process of typewriter repair and cleaning is not at all what I imagined. I pictured Mr. Lundy in a leather apron with a magnifying lens disarticulating and painstakingly scrubbing every tiny piece of my typewriter and then putting it all back together with a screwdriver half the size of a toothpick. I was only half right. The shell of the typewriter comes off, and the parts that require replacing are removed, but the typewriter itself remains mostly intact as it is immersed in a solvent bath to loosen up the schmutz (in the case of my machine, 67 years' worth of gunge). The next step is one I could not have guessed in a million years: the machine is baked, yes, BAKED. This hardens the the gunge that was loosened by the solvent bath into a crust which then readily flakes off. After that, broken, misaligned or bent parts are repaired or replaced and then the typewriter is oiled, the shell is replaced and bam--you have a working machine. Some folks may not find these details interesting, but to me they are nothing short of miraculous.

Mr. Lundy's craft requires the utmost care, precision, and--let's be frank--a huge fund of knowledge. Just as with automobiles, there are dozens of makes and models of typewriters, each with their own unique set of technical specifications for repair and maintenance. And since many of the companies that originally manufactured these machines no longer make them, they likely no longer employ people who know how to repair them. That means Paul Lundy has to be able to fix everything that people bring in for servicing from turn of the twentieth century models to IBM electrics made in the 1970's--and more.

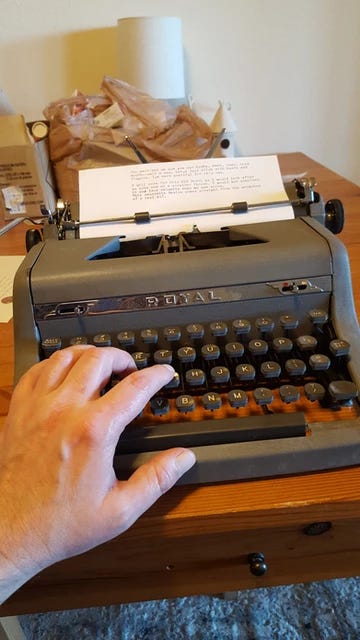

In addition to discussing the history of the shop and typewriter repair process, Mr. Lundy showed me some typewriters that people donated to him and those that for one reason or another he couldn't sell, and thus he was offering for free--FREE! That's right, I walked out of there with a FREE typewriter, so even though I won't see my baby (or Great Grandmother, depending on how you look at it) until July, I have a new charge to care for. And what a fascinating one at that! After doing some research, I discovered that I am the proud owner of a 1953 Royal Quiet DeLuxe--one of the only typewriters I've encountered with it's own wiki page. Why? Because it is the most expensive typewriter in the world!

Or some of them were at least. Royal made gold-plated versions and gave them out to writing contest winners and loyal employees (oh, weren't those the good old days?). Supposedly Ian Fleming wrote every James Bond story on his custom-crafted, gold-plated model except Casino Royale. Ernest Hemingway used one too. Despite these stories, it's obvious from it's diminutive size and sturdy build (see the photo of my hand for scale) these devices were primarily built as workhorses, not show ponies.

With a proper case, this typing machine could accompany me on the most far-flung desert sojourn with ease (though even with it's decreased volume, its "voice" might inhibit the deer and the antelope from playing). Those who know me know I'm not one to get gushy over material objects, but it's incredible to think I just stumbled into owning a piece of history with such a legacy. Although the carapace has a few dings and scuffs that show its 68 years of life, the keys work, the ribbon has been replaced and it functions remarkably well. Unlike modern phones and computers, machines of bygone eras were designed to last more than a year or two--or a decade or two. I can't wait to begin using it!

Why Use A Manual Typewriter?

So what's the point of using a manual typewriter when computers are so ubiquitous? With the advent of sophisticated autocorrect, it could be argued that's it's possible to even use a smartphone as a primary means of writing (and for folks who rarely do more than text, it is), so why typewrite? First off, typewriters quite simply are reliable, practical tools. They have durability, longevity and utility far beyond what most people are aware of. The two I own are perfect, typical examples. Aside from needing some long-overdue maintenance, my Olympia SM4 DeLuxe has survived almost 70 years of use. Ditto my new little Royal Quiet DeLuxe. Even the small portables are built as sturdy as tanks. They are clearly designed to withstand oodles of abuse. There is no question that with a bit of TLC, both of these machines have many more years of use ahead of them. I certainly did not bring them home to be ornaments.

Another common myth is that typewriter ribbons aren't sold anymore, or are hard to come by. I was surprised to learn that most typewriters from the 1950's onward use a universal ribbon, making sizing easy. Also, it's not necessary to hunt down a specialty store to find ribbons (but it's nice to support small business when and wherever you can); they're sold on Amazon, ebay, even Walmart and Staples carry typewriter ribbon! (Staples even lists brand-new portable typewriters for sale by Royal for $299) That brings me to my last point, typewriters are economical for long-term use. The average cost for a ribbon is $5-$12. Though it varies depending on the quality of the ribbon and the material used (silk is best), as noted in this helpful article in Typewriter Review. A person can produce between 100-720 pages from one ribbon. Printer ink, on the other hand, costs between $20-$60 and yields about 220 pages.

For the Love of Raw Writing

Computers, word processing tools and smartphones are indispensable. The internet did not exist until I was 18 years old (yes I'm THAT old) and it didn't become convenient to use until my early to mid-20's. That means I spent hours as a young man slouched with a massive dictionary flopped in my lap to correct my atrocious spelling. While editing is still a tedious chore, I'm still as grateful for spellcheck and other word processing tools as I am for clean-flowing tap water and air conditioning.

But our word processing tools have advanced to the point where they are on the cusp of doing the writing for us. Essentially, in tandem with more primitive algorithmic tools like the FOG Index, they are dumbing us down and robbing us of our very ability to think. Artificial intelligence (AI) software like Grammarly, autocorrect, the "suggested phrases" and canned responses insidiously pushed by social media bots and the "grammar checker" function on Microsoft word go far beyond checking my spelling. They attempt to alter my voice, flatten my writing style, and homogenize my use of language. In essence, they work to remove "me" from my own writing, ostensibly to make my writing "better," and to make me sound like everyone else and ergo, to make us all sound exactly the same.

A manual typewriter is an excellent, subversive device for disconnecting from the thought manipulation of sophisticated artificial intelligence software.

The presence of this software is flawed, because we can still detect it and be annoyed by it, but the technology will soon evolve to a point where it can mimic our thought and behavior patterns in fewer and fewer keystrokes. It will eventually reach a point where its influence is so subtle that we are unaware it has changed the way we think and communicate. When the event horizon of that moment is reached, it will be no exaggeration to say that AI will be able to control our minds, and the thoughts we think will no longer be our own.

Working on a typewriter places you in a space where nothing has the ability to manipulate your thoughts or interfere with your process. There is not even a screen separating you from your words.

Interestingly, as our devices become "smarter" and more interconnected, they have become more unwieldly and difficult to control. Whereas, I used to simply be able to plug a USB cable from my printer into my laptop in order to print a document, with my latest generation HP OfficeJet all-in-one printer/scanner/copier, I'm required to do it via Wi-Fi, which necessitates that I have an online account with them, be signed in, be subjected to pop-up's, unwanted updates, and opt out of their spam. From a mechanical perspective, the machine itself is junk. It often jams, smears the ink, has a tiny paper tray and its computer often fails to recognize compatible, ordinary printer paper. Every time I use it I cross my fingers and hope for the best.

A typewriter is simplicity itself.

A page is rolled onto a platen (the thing that looks like a cookie dough roller). It's manually aligned. Your finger strikes the key. A physical, metal typebar rises and strikes the ribbon, leaving an ink outline of the letter or symbol on the piece of paper. Repeat. That's how a typewriter makes words physical.

Speaking of corporeality, another feature of manual typewriters I love is the mechanical keyboard. Even when writing using my $500 laptop, I use a crappy external Dell keyboard I bought from Goodwill for $5. I do so because The keys are large, thick, clunky and I can really beat the hell out of them. I am a troglodytic, hunt-and-peck typist known for hitting keyboards so loudly that in graduate school my classmates--not my teacher--insisted that I take essay tests in another room. If I was forced to use the dainty keyboard attached to my laptop I'd be changing laptops more frequently than I change my socks.

Even the "quiet" Royal Quiet DeLuxe exudes a kind of ox-like, bestial quality that practically begs you to strike its keys with a confident finger. These old manuals are not smartcars and Teslas. They are trucks with studded tires with pipes that make noise--they even produce "fumes." All through Mr. Lundy's shop and in an aura around my machines is the effluvia of old books, the must of venerability, an olfactory charisma that--however much I love and appreciate it--my crisp Lenovo laptop could never hope to compare to.

Perhaps these observations sound a bit overwrought, but for me, writing has always been a distinctly physical process as well as an intellectual and emotional one. Some folks may find banging on the keys to get their message across irksome. For me, it is grounding. Acknowledging and reveling in the tactile qualities of writing that bring me pleasure adds to the joy of something I feel born to do: write.

What You Can Do With Your Raw Writing Machine

Which brings me back to my point. Owning and using a manual typewriter does not mean becoming a Luddite and abandoning your laptop or smartphone; it simply offers an opportunity to remove barriers between imagination and expression of ideas. After getting those ideas on paper, you can then transcribe them into ye old laptop where the editing can commence. It places a wall between writing and editing, which can be an invaluable tool for the production and expression of unfiltered thoughts and ideas.

As much as it changes, the first draft is sacred. It's the expression of an idea and the creation of worlds through words that heretofore did not exist.

Keeping a machine specifically designed to put first drafts on paper does not seem like an extravagance, but a necessity. And for those who frown on the tedium of transcription, the act of transcribing is itself a valuable editorial process that is usually lost to most of us who use word processing software. In fact, the idea of a "first draft" is a bit of an antiquated misnomer, since most of us edit as we go. I think of transcription as a three-step process: it involves reading, then writing and changing what you've already written in your first draft.

What Else Can You Do With These Glorious Machines?

However, the typewriter is more than a first draft machine. As an epistolary-style historical fiction writer, the aesthetic qualities of font and typeface are even more important to conveying a sense of authentic time and place than an image on the cover or inside the book. The font, the letters, the words form inextricable visual cues for the reader and with epistolary writing (telling stories through the use of letters and documents) the font itself becomes part of the narrative. That's why in my most recently book Squabble of the Titans, Recollections of Roosevelt and His Rival's Hunt for Bigfoot in the Olympic Rainforest I painstakingly chose multiple typewriter fonts applicable to the era; they help lend the fake documents and journal entries I've written an air of historical authenticity.

With a bit of creative ingenuity, it's possible to integrate the page layout functions of your computer's software with the authenticity of a manual typewriter. Had my Olympia typewriter been working at the time I wrote the novel, I would have used it to re-write passages from my book using antique parchment paper, then scanned the pages and formatted them into the document. Since I didn't have it at my disposal, I completed the same process using free, open-source public domain vintage typewriter fonts available online. Although a wider variety of fonts were available online, there are still distinct advantages to using a manual typewriter. The key strike leaves a variable, inexact and usually deeper impression in the paper, which is difficult to mimic with the crisp perfection and uniformity of a digitally generated font.

Sometimes this veneer of imperfection is the very aesthetic quality that lends character to a document, even when it includes strike-throughs and other typos. Part of my technique for developing "authentic" weathered-looking historical documents was pouring coffee on them, tearing them, and crumpling them up in a ball. It all adds dimensionality and personality to a what a white, flat piece of paper with a Times New Roman font cannot.

Tasks that, in an ink jet printer, require complex feats of alignment such as printing labels or addressing envelopes can also be far more simply and elegantly completed using a typewriter. One could write a book in its entirety, scan it and reproduce it page by page. Or simply revive the lost art of writing a letter to a friend.

Right Speech & Slow Words

Buddhists have a principle known as "right speech." Broadly speaking, I understand that to mean speaking with kind intent, truthfulness, integrity, and the desire to do no harm. How easy our social media and texting and emails channels make it for us to spout whatever angry nonsense is in our heads--some of which should be withheld for the good of ourselves and others (an old fashioned virtue known as "forbearance" which is rarely practiced anymore).

A Western concept relating to right speech is that of the slow food movement, which is part of a wider, ongoing trend to slow down and mindfully enjoy life by increasing our awareness of simple pleasures, essentially giving efficiency and our sick "time-is-money" capitalist ethos the middle finger. The slow food movement asks the question, wouldn't we savor the experience of eating a meal if, instead of stuffing our pie holes as expeditiously as we can, we took time to taste our food, converse with friends and family and savor both the meal and the experience?

A typewriter offers us a vehicle to lessen the pace of our communications, to think before we speak, to choose our words with care and precision--in essence, to enact a "slow words" movement. A typed letter is an excellent compromise between a hand-written letter and a text, because it's faster to write than a hand-written letter but it is still personal--and at this stage of our society, very rare. Letters take longer to create, send, receive. Therefore, they generate a sense of anticipation that texts and emails cannot. They are special. And because they exist in physical space, they can be decorated, stored and retrieved without dependence upon a computer to conjure them back into existence.

If something catastrophic happened to our power grid or satellite systems, the vast majority of us would lose all of our tangible keepsakes: no more photographs, letters or memorabilia of any kind from our loved ones, because for the past twenty years people have ceased to keep anything in the corporeal world.

What faith we put in our devices and systems that we will be able to safeguard our most precious moments in perpetuity!

* * *

By now, it should be clear that a typewriter is more than a machine. It is an instrument of freedom. While I could live without one, I cannot see why I would ever choose to. But then, words are as important to me as wood is to a carpenter. And they are just as beautiful in the raw. Nothing gives form, substance and clarity to words in the raw like a typewriter does. It reveals their very grain.

And with that, it's time to go and write a thank you note to Mr. Lundy using my new Royal Quiet DeLuxe.